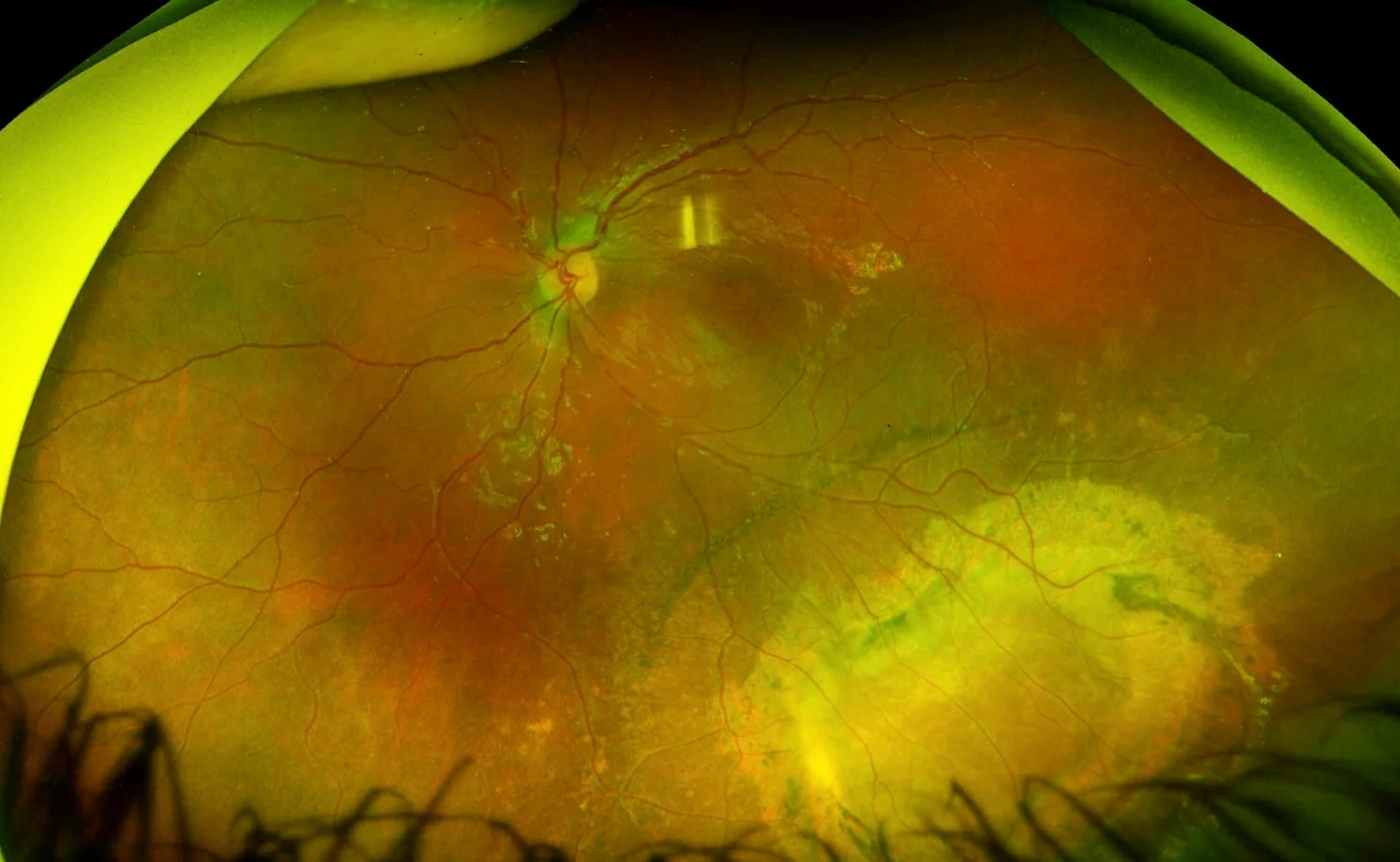

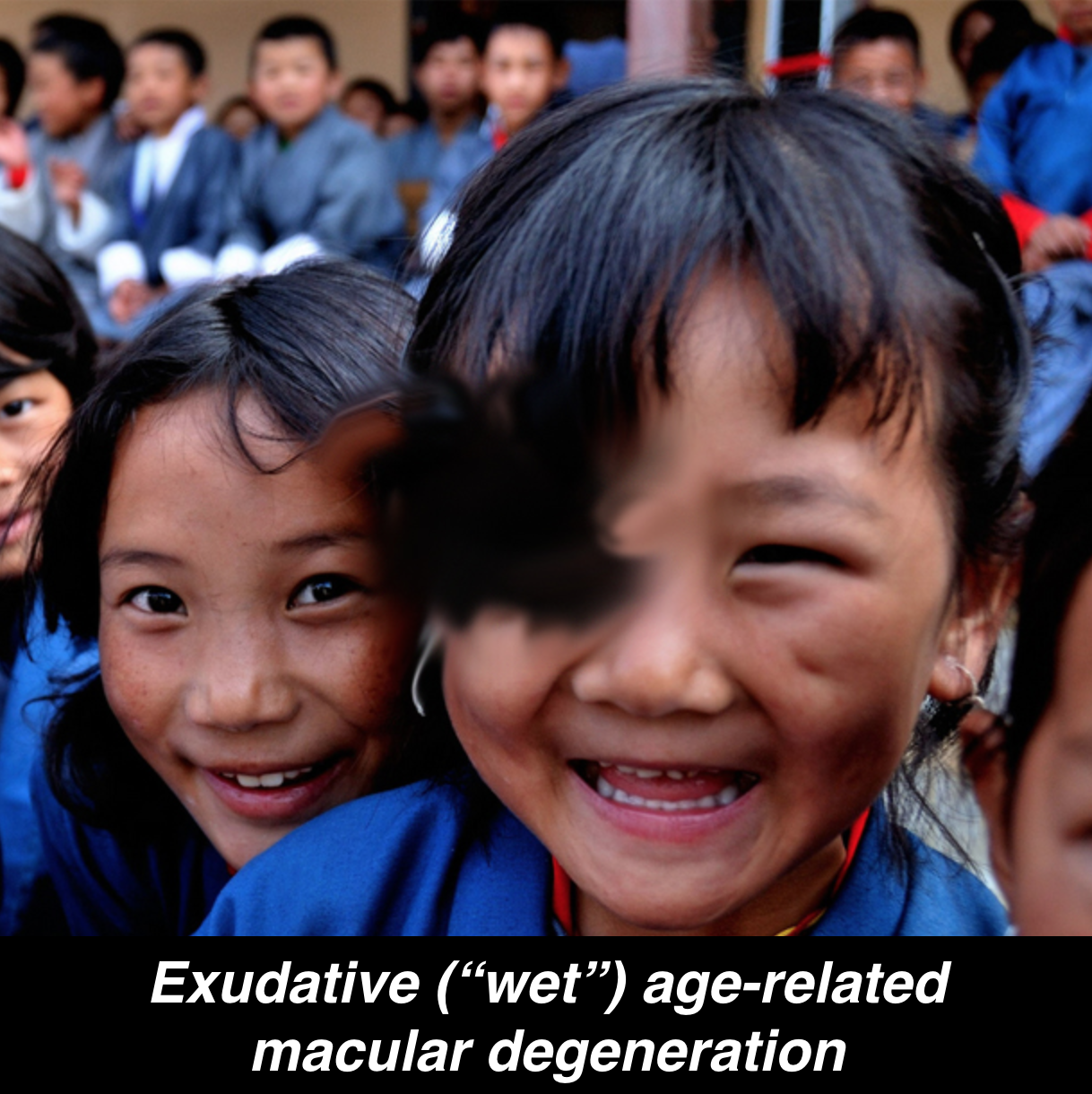

An article published online today in The New England Journal of Medicine has quickly gained recognition within both the scientific community and among the public. The report, published by Ajay E. Kuriyan, MD and colleagues describes three elderly women with macular degeneration who were treated at a so-called "stem cell clinic" in South Florida with the hope that they would regain vision. Tragically, not only did none of the three have any improvement in their vision, but each suffered severe, permanent vision loss as a result. Each went from having vision good enough to drive to being legally blind.

This clinic, operated by an entity known as U.S. Stem Cell, claims to have treated many patients with all sorts of different ailments (e.g. knee injuries, heart failure, neurological diseases) with "stem cells," which they purport to obtain by removing fat from the patients' own bellies and then purifying this fatty tissue into stem cells (author's note: I have no idea whether they obtained actual stem cells or not, and I'm highly suspicious that whatever they produced wasn't exactly "100% pure," shall we say).

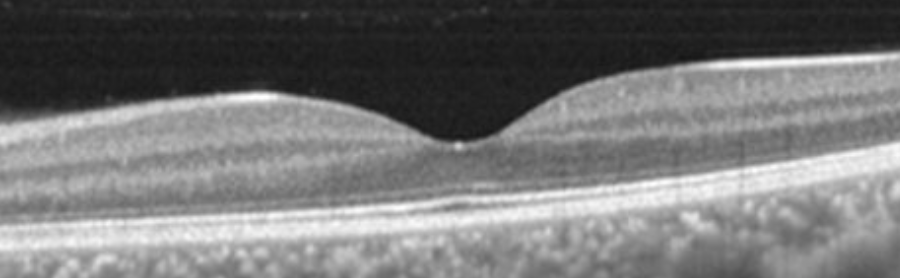

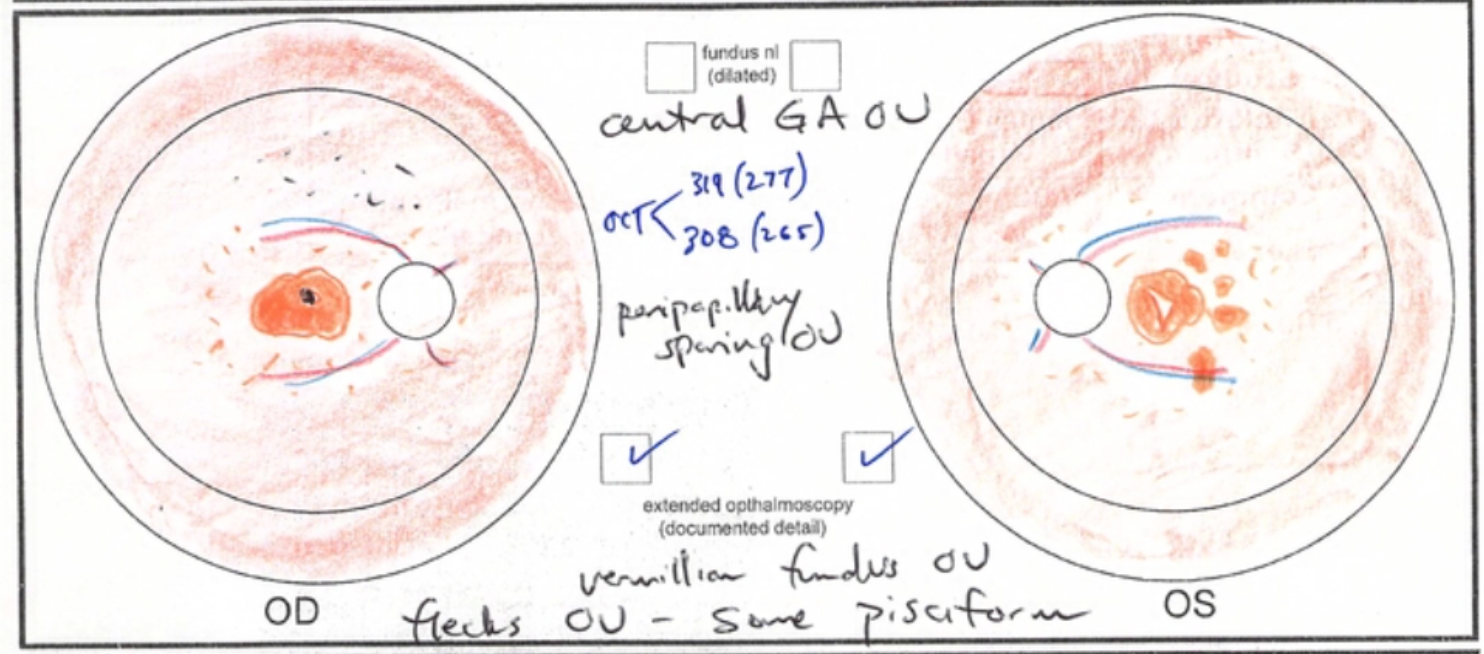

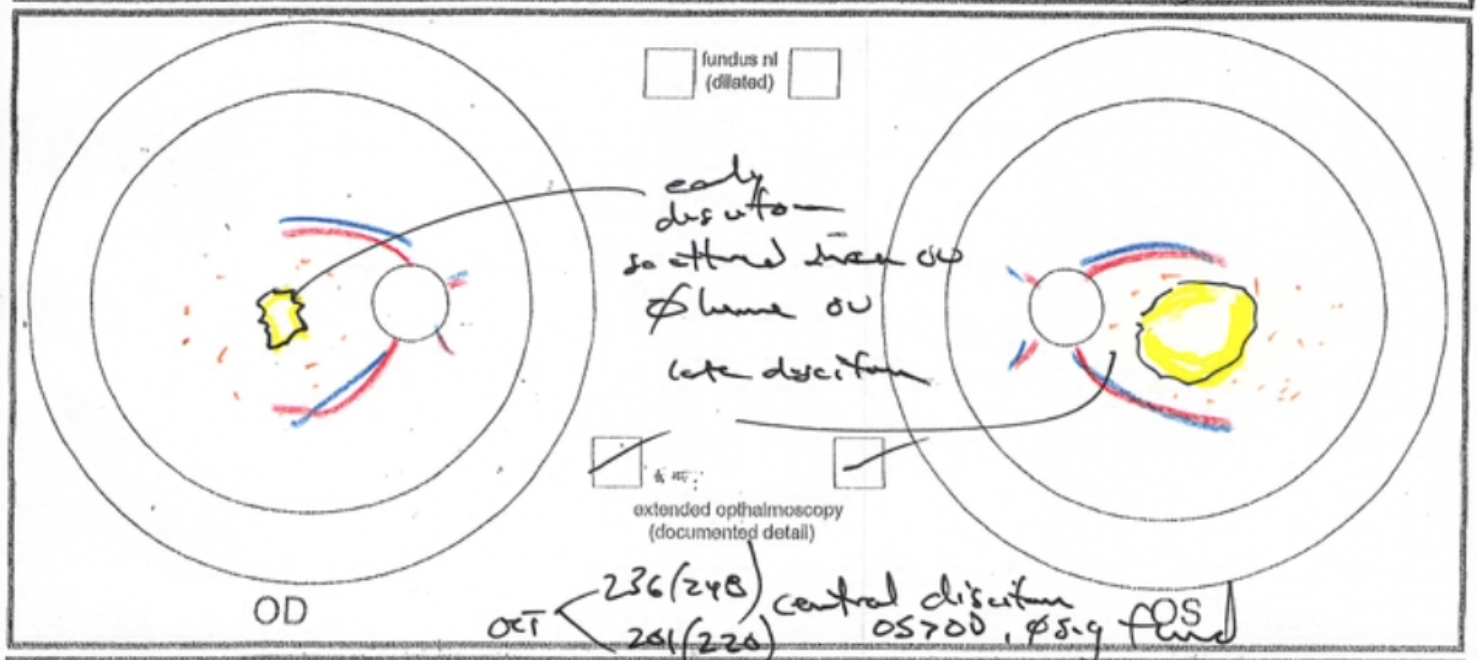

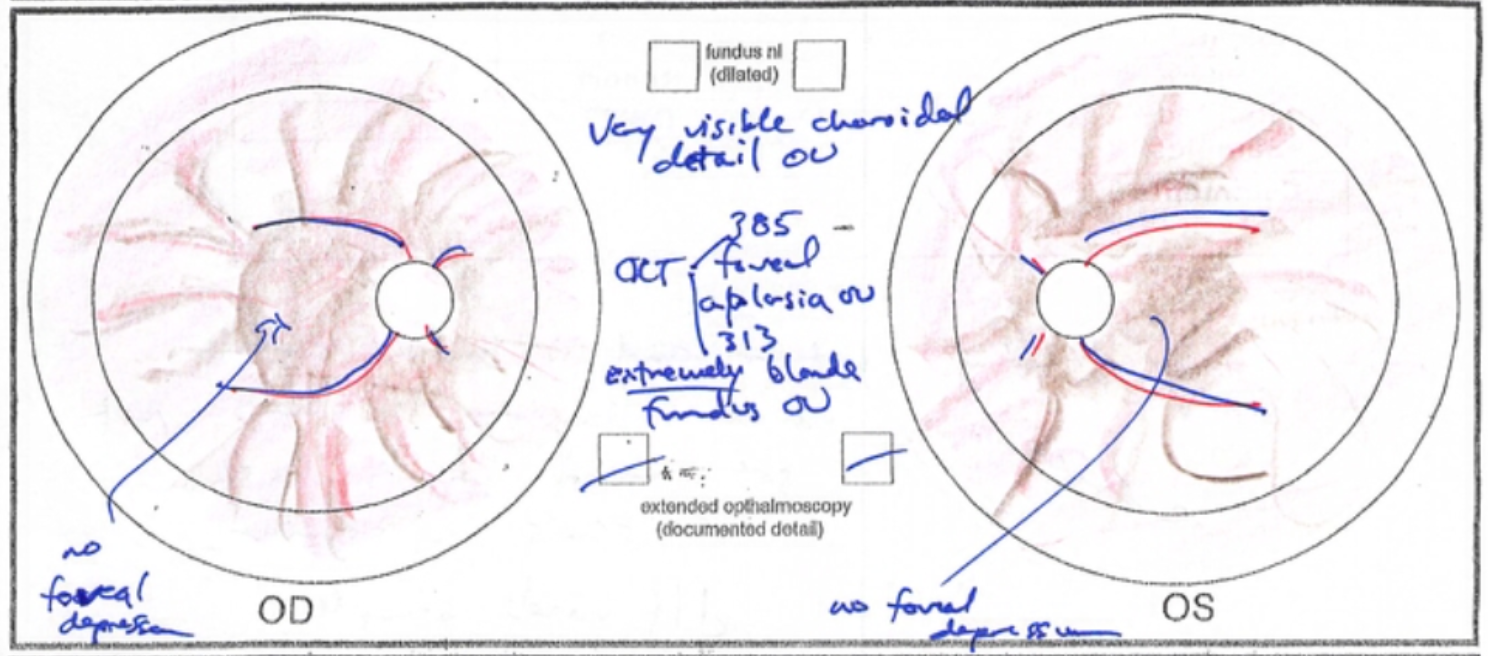

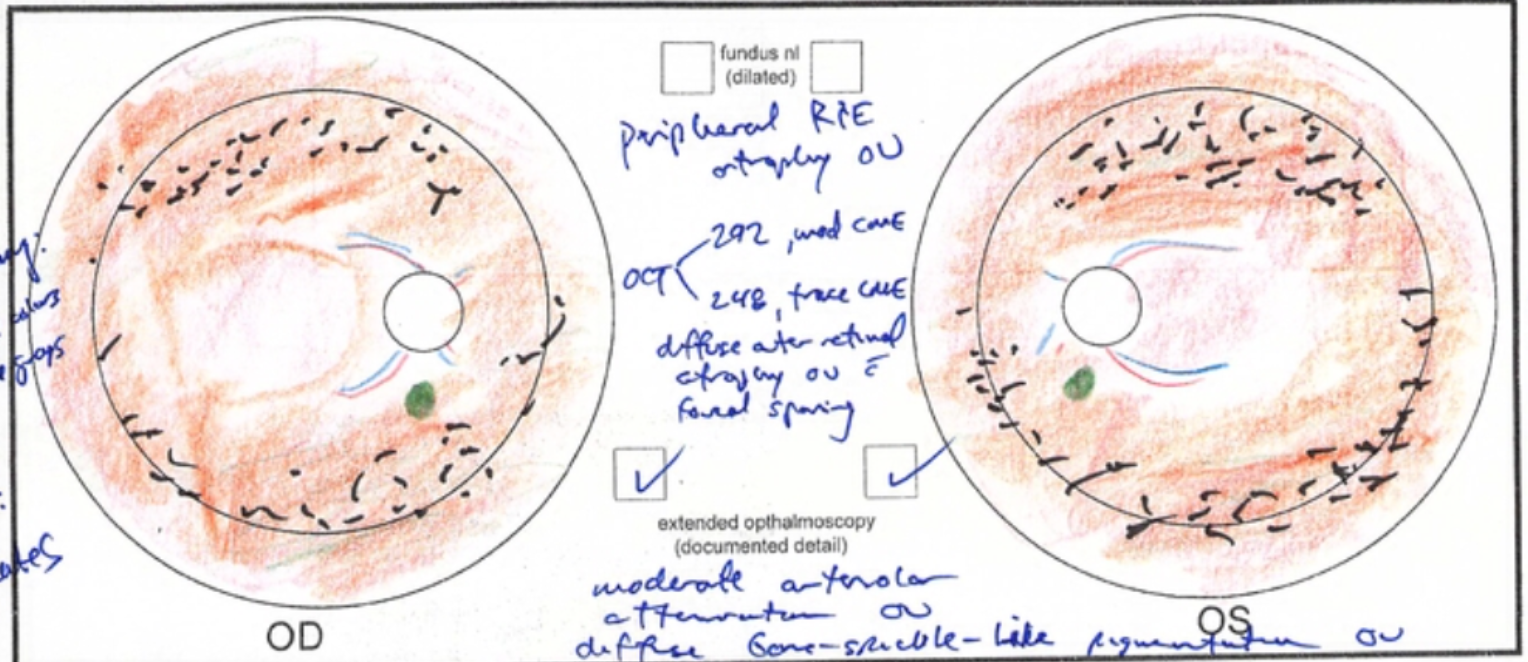

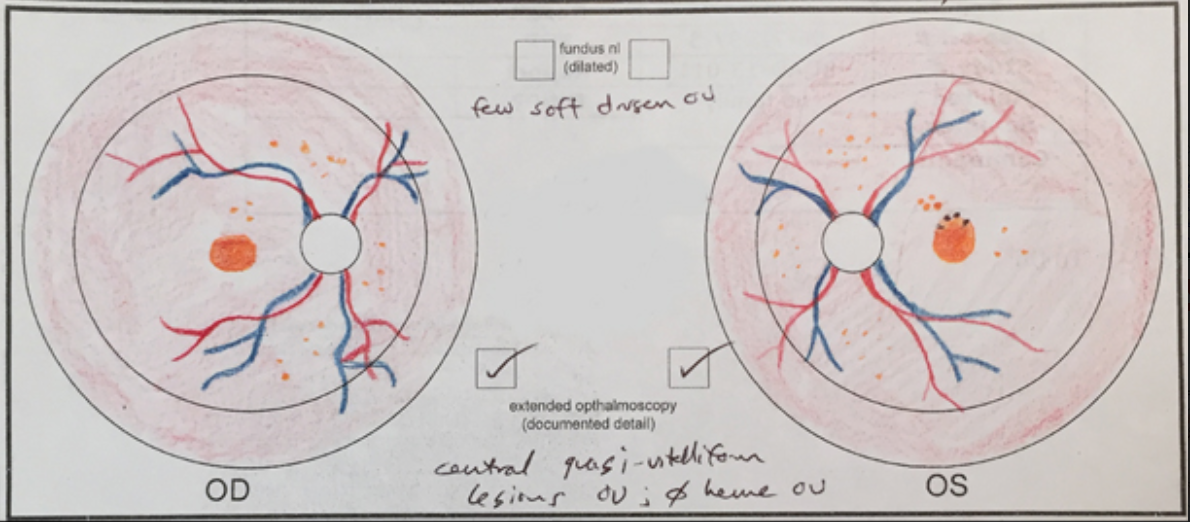

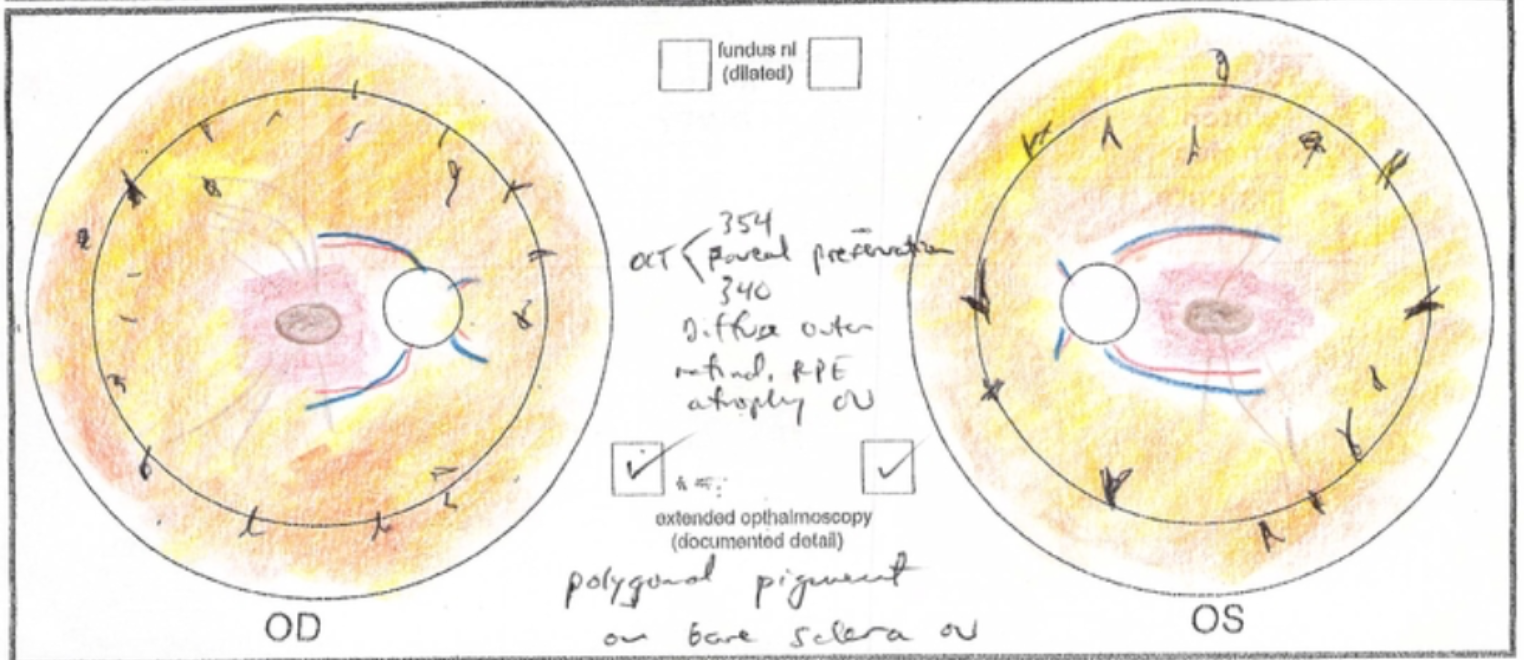

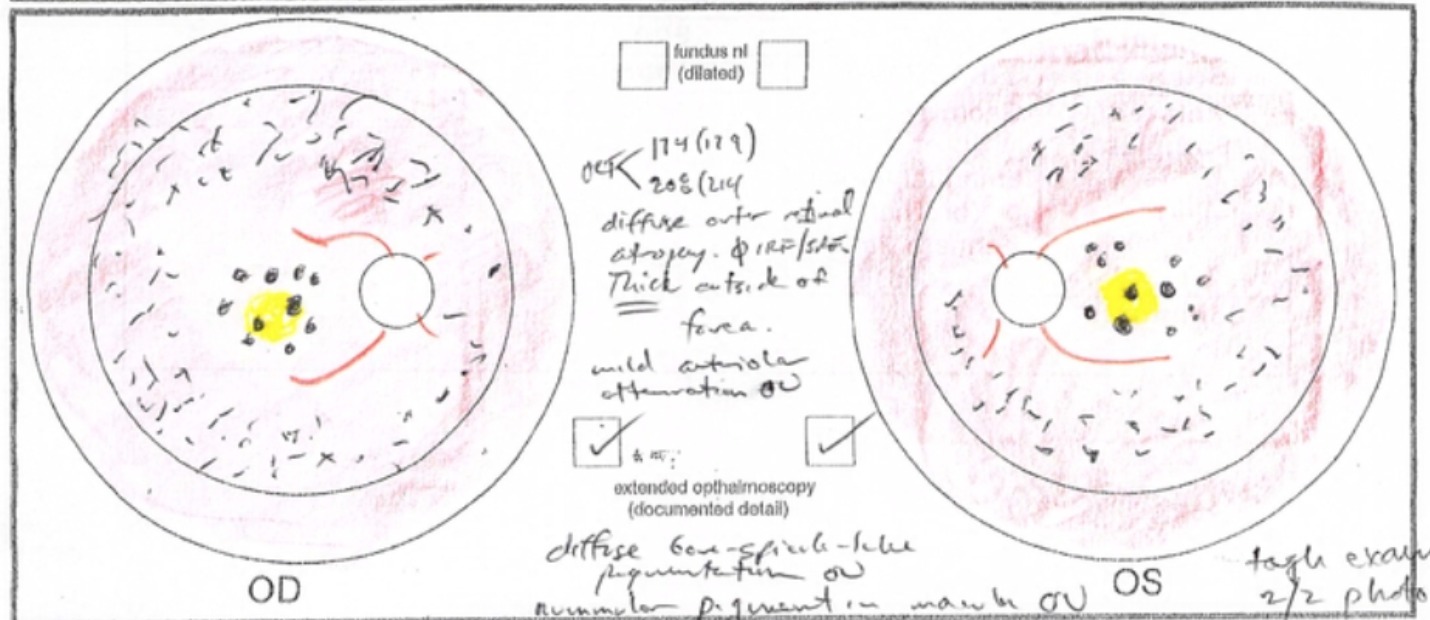

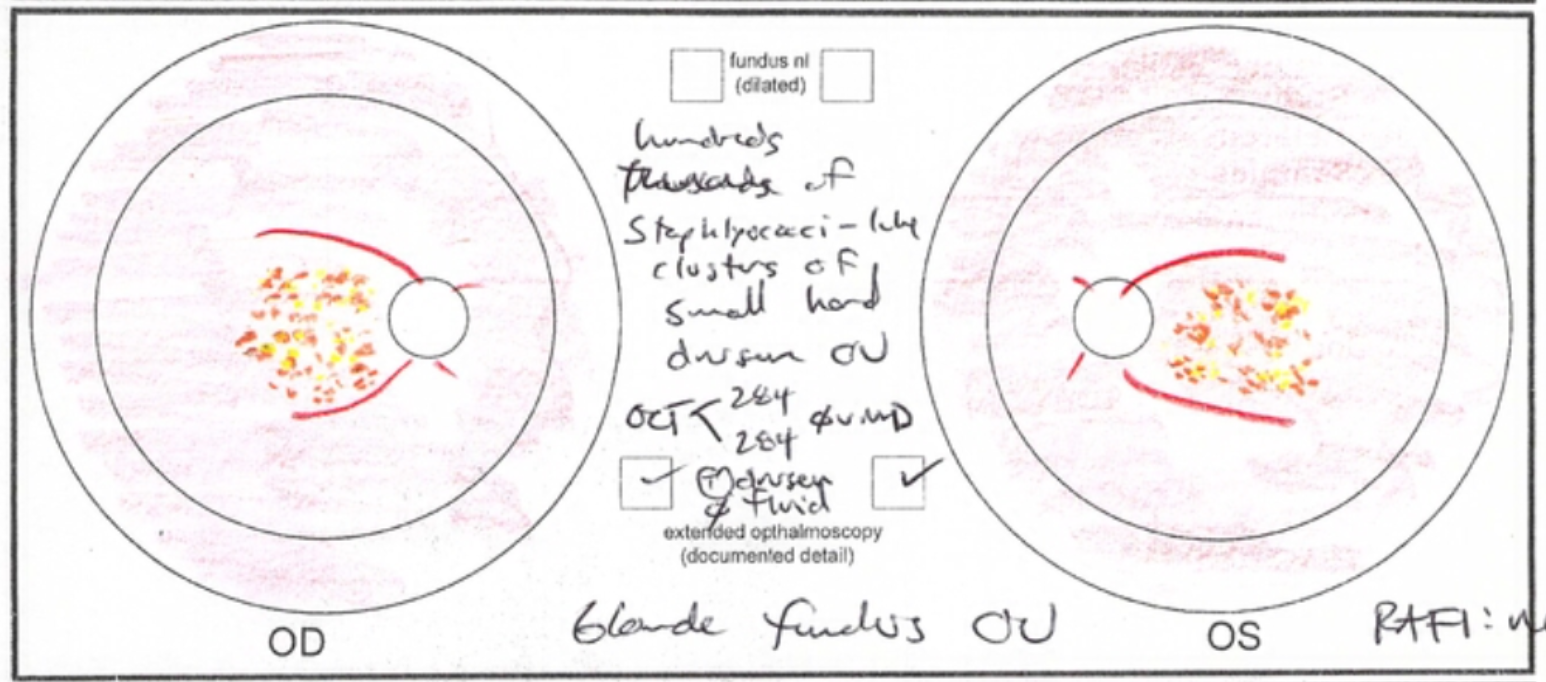

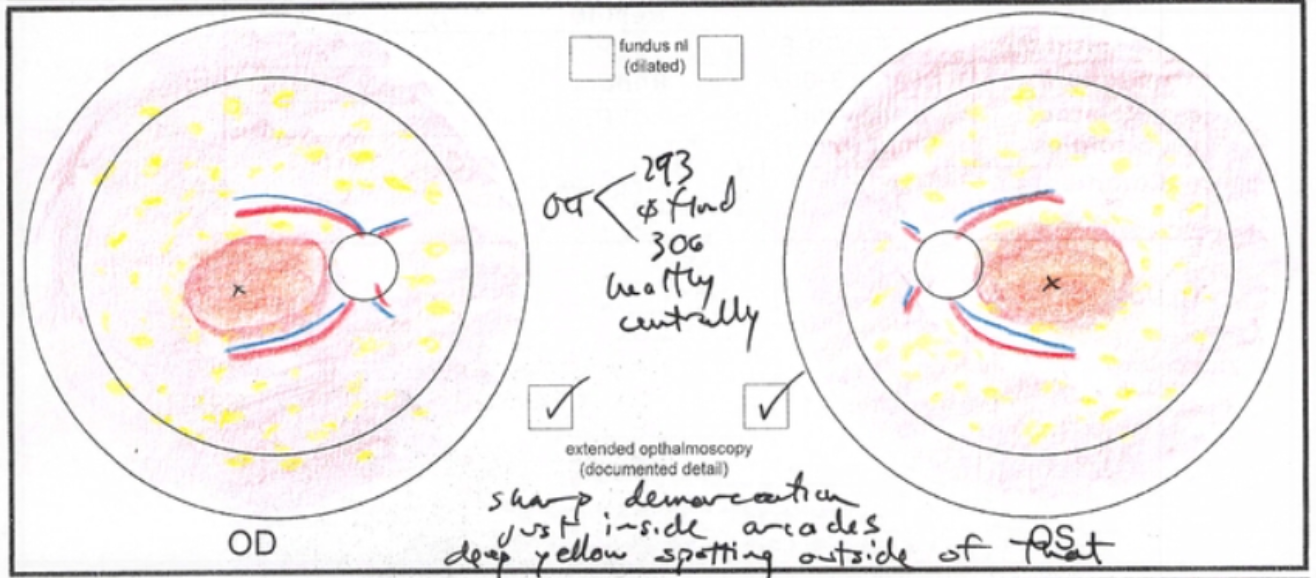

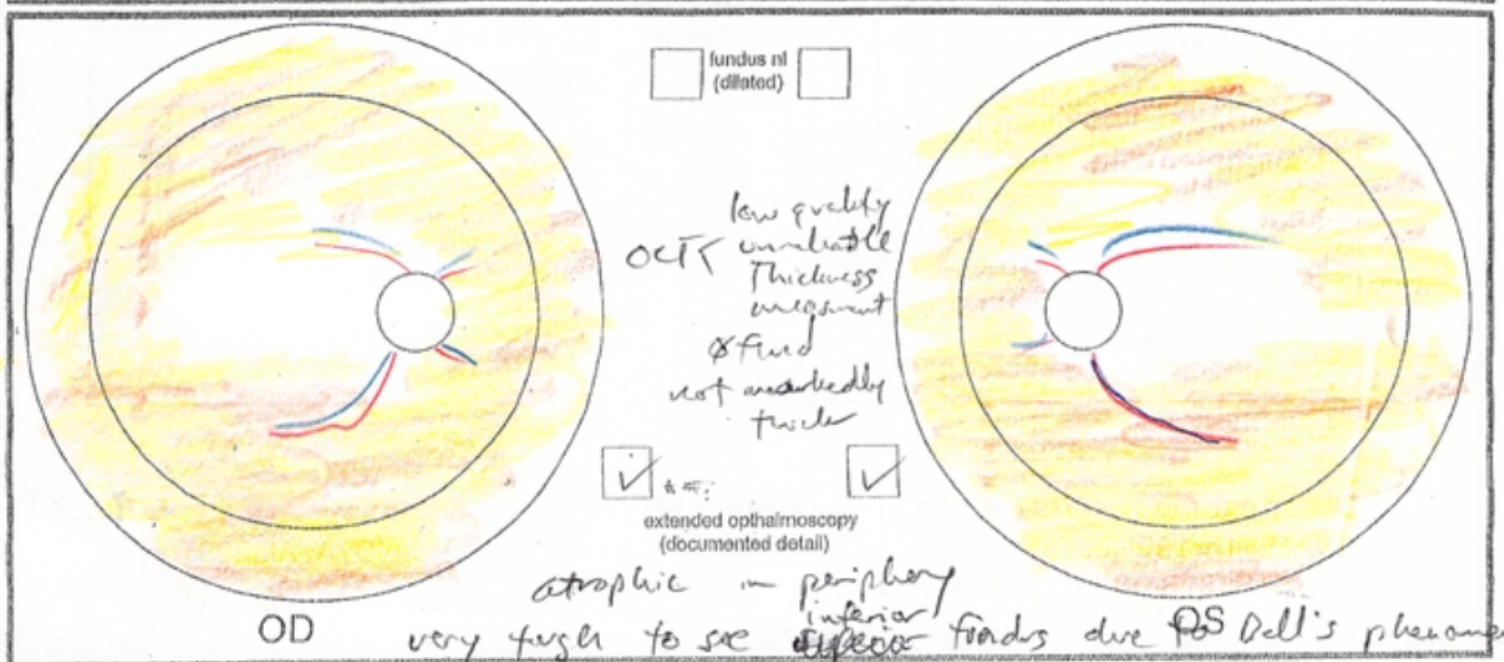

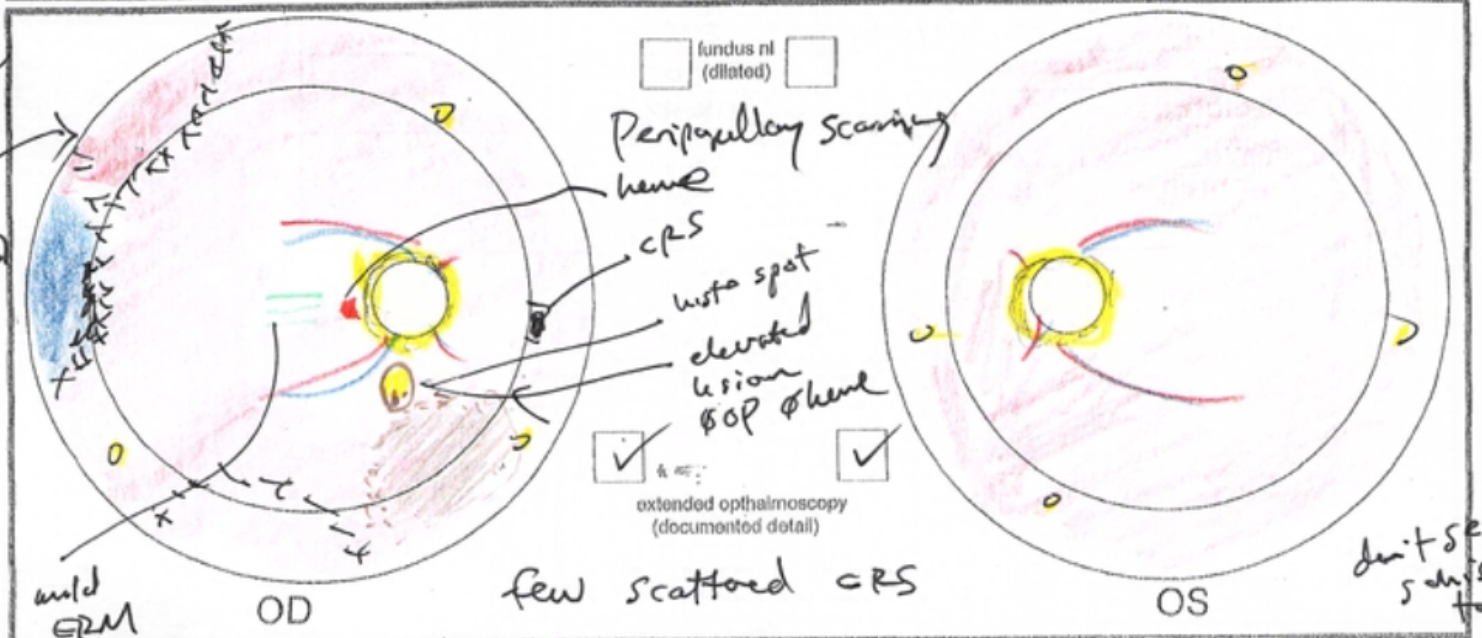

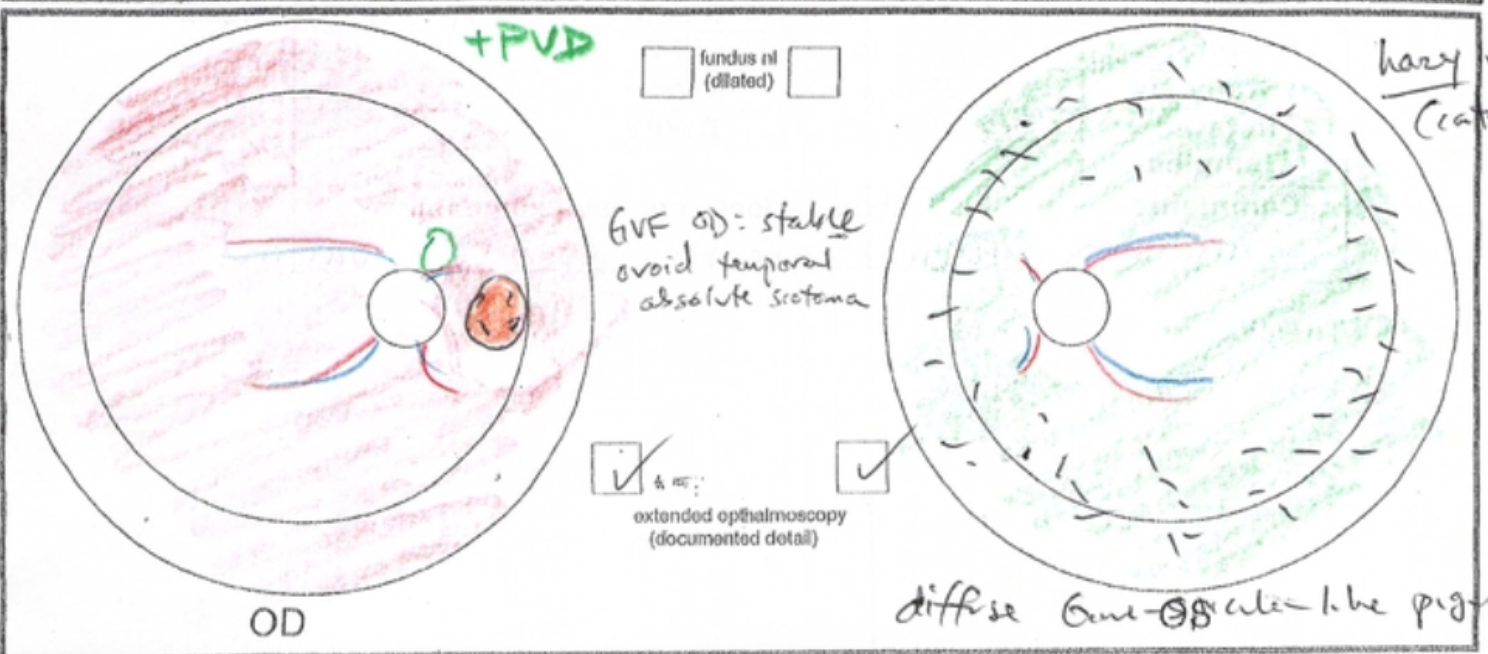

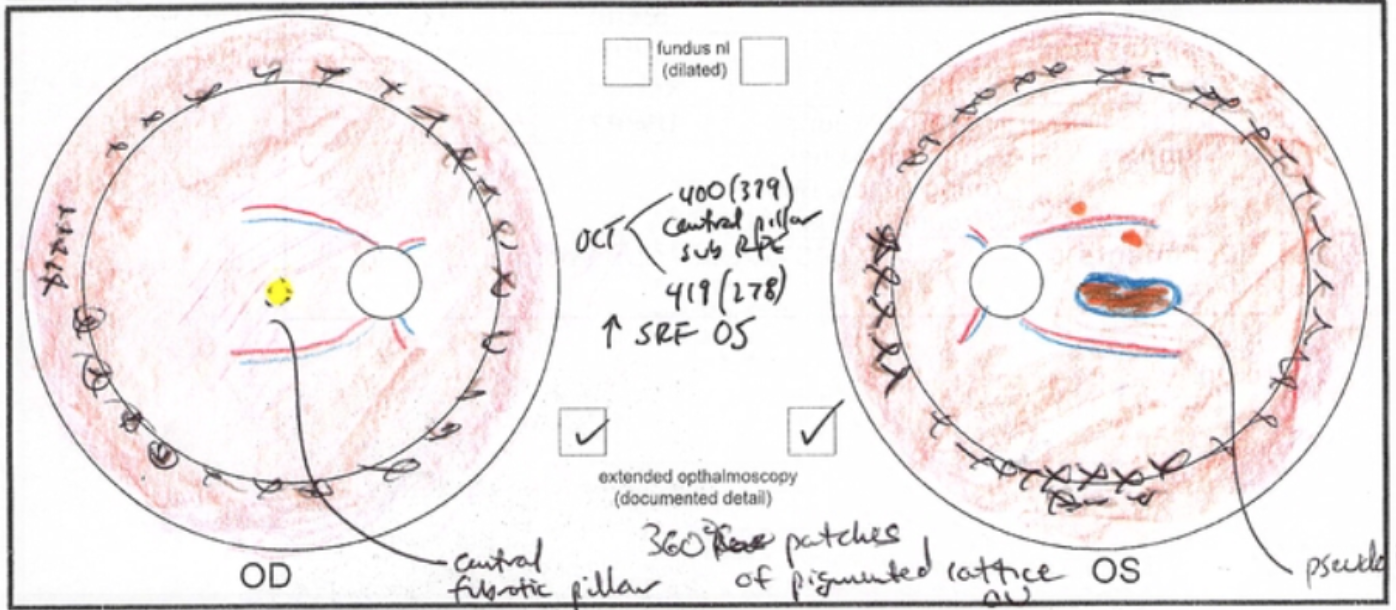

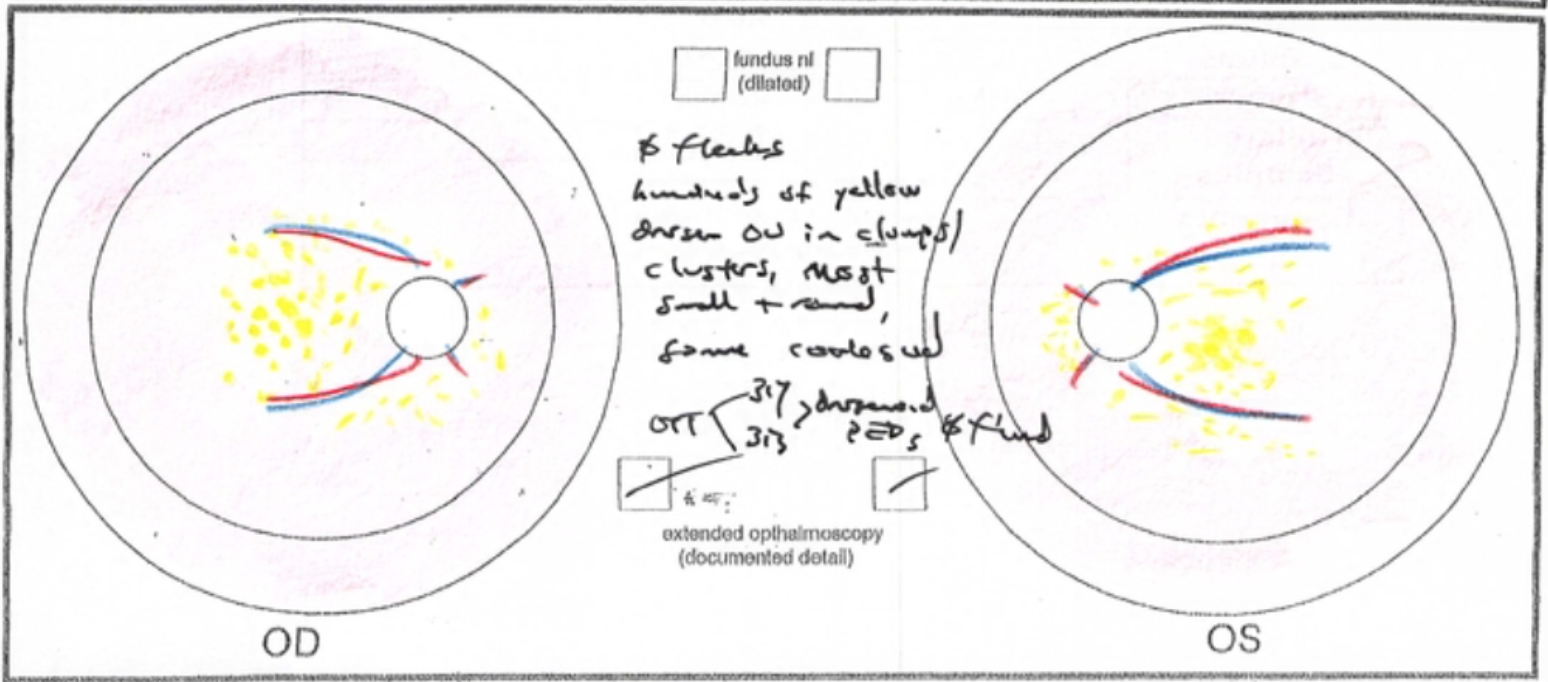

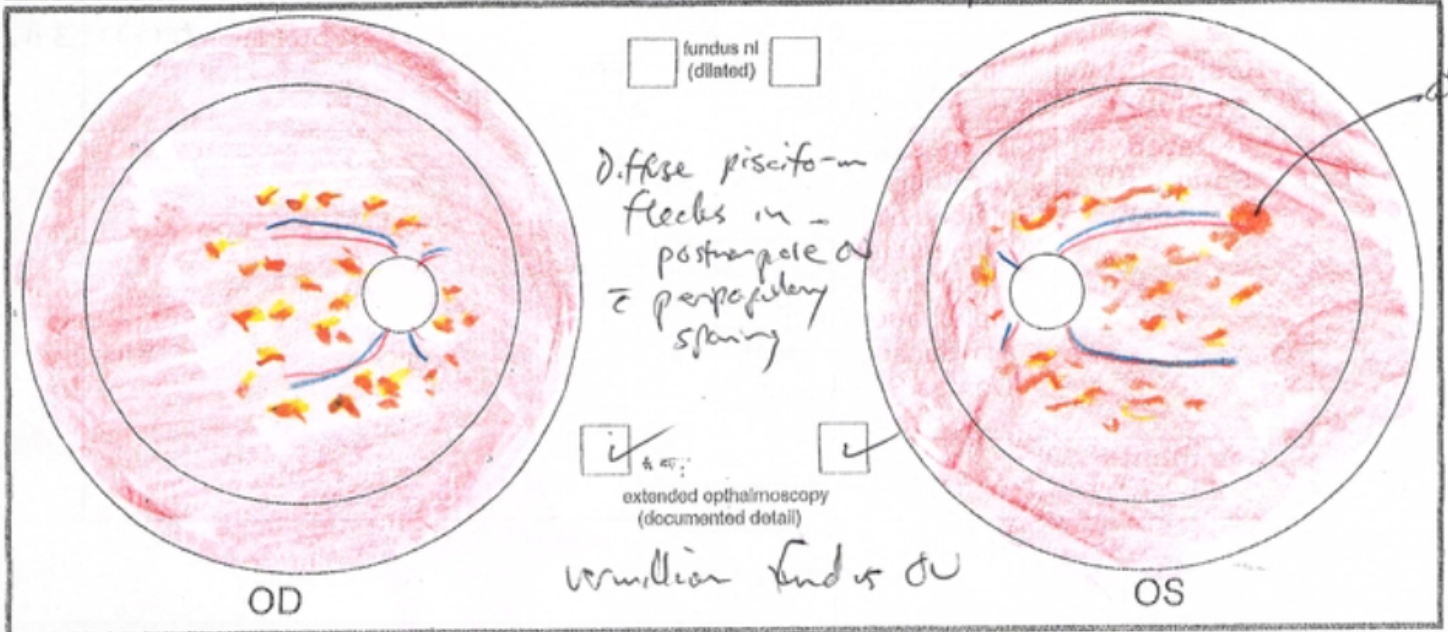

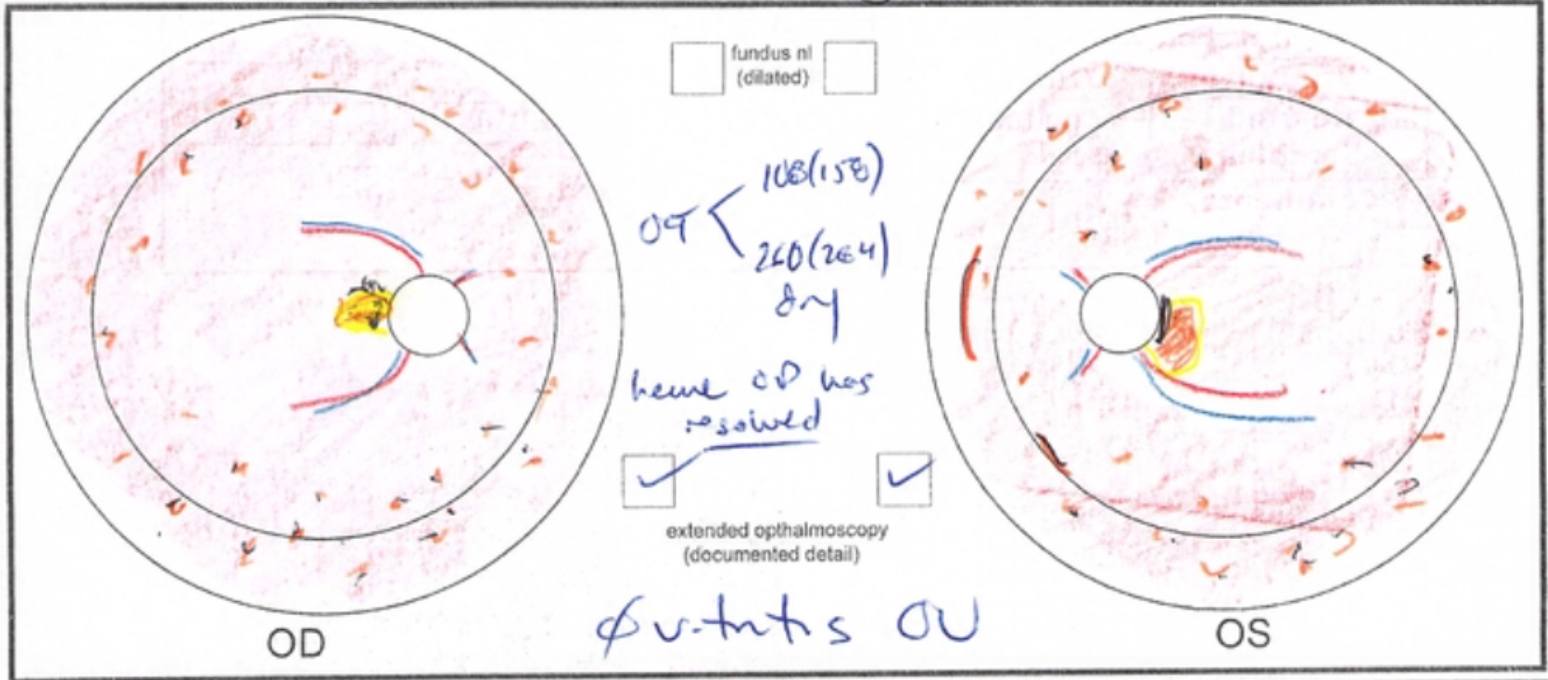

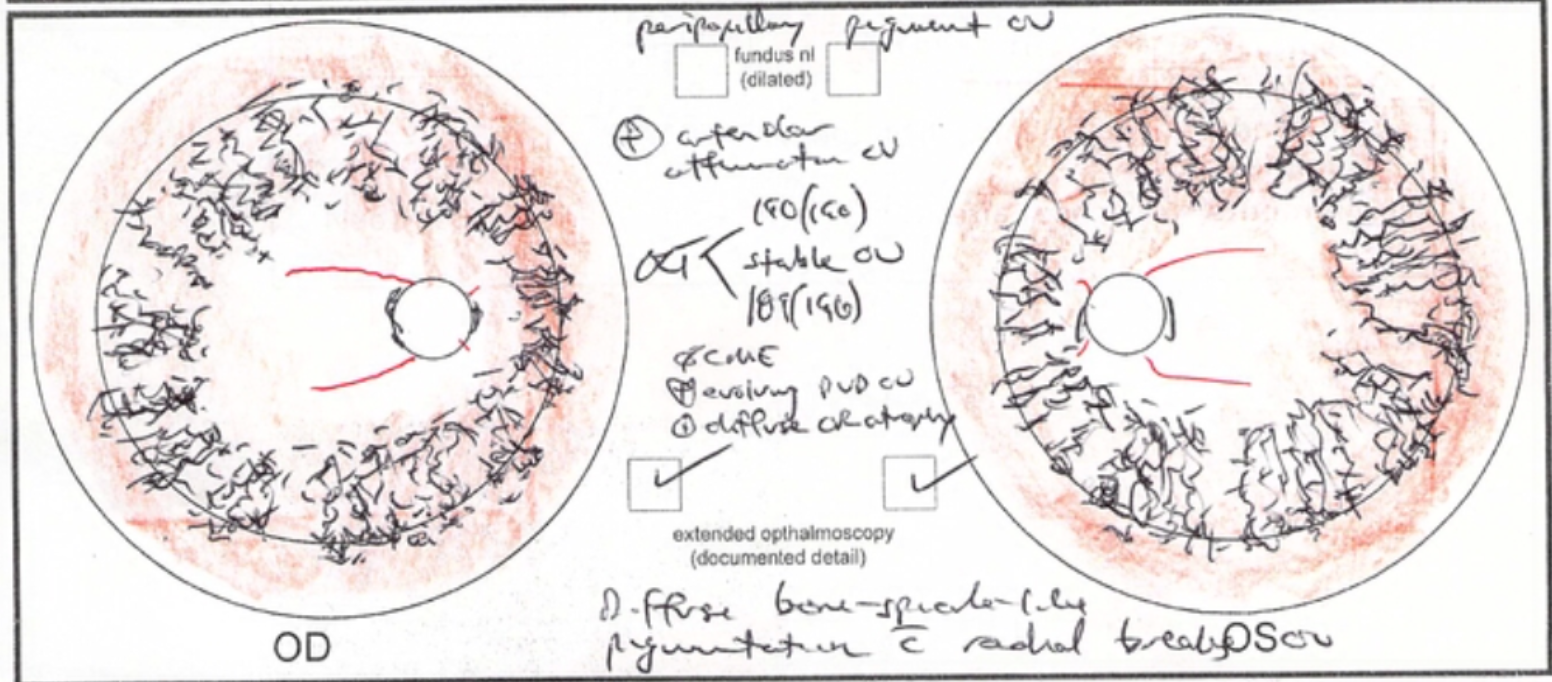

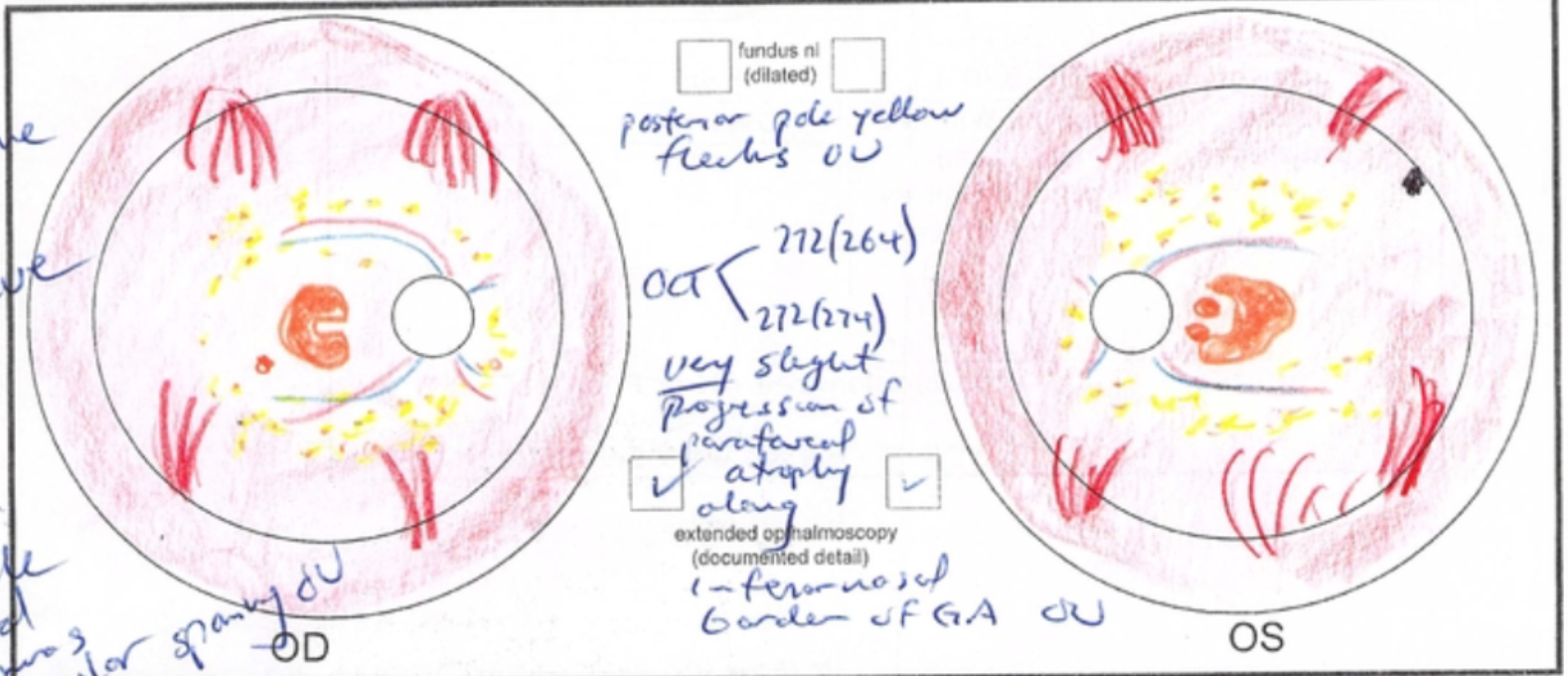

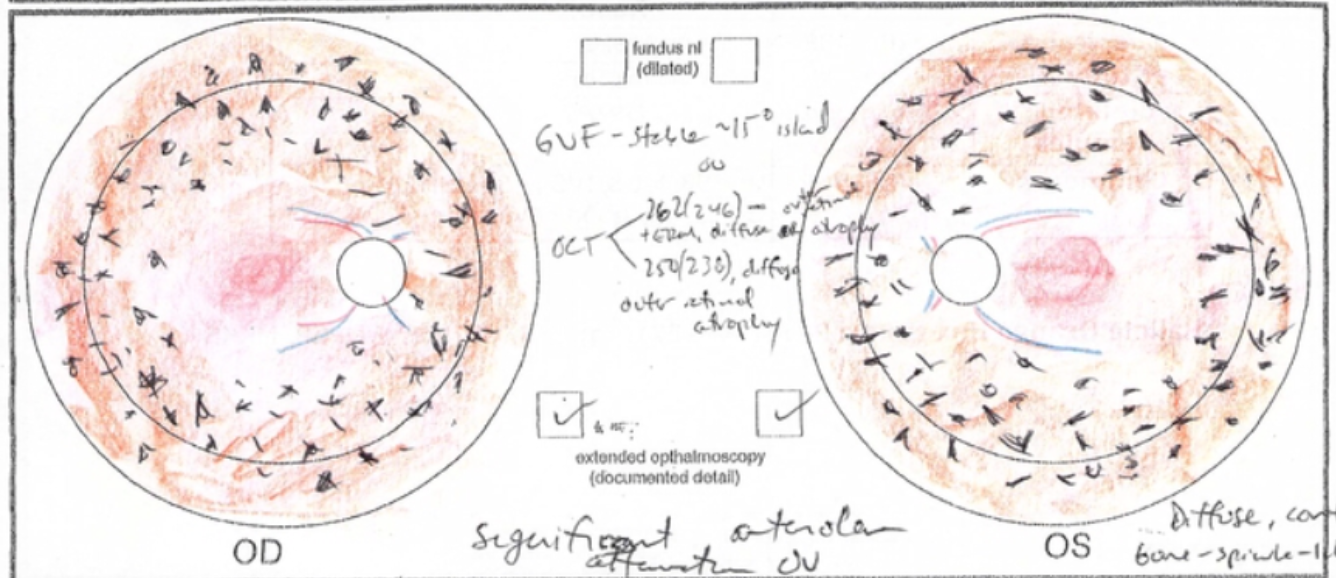

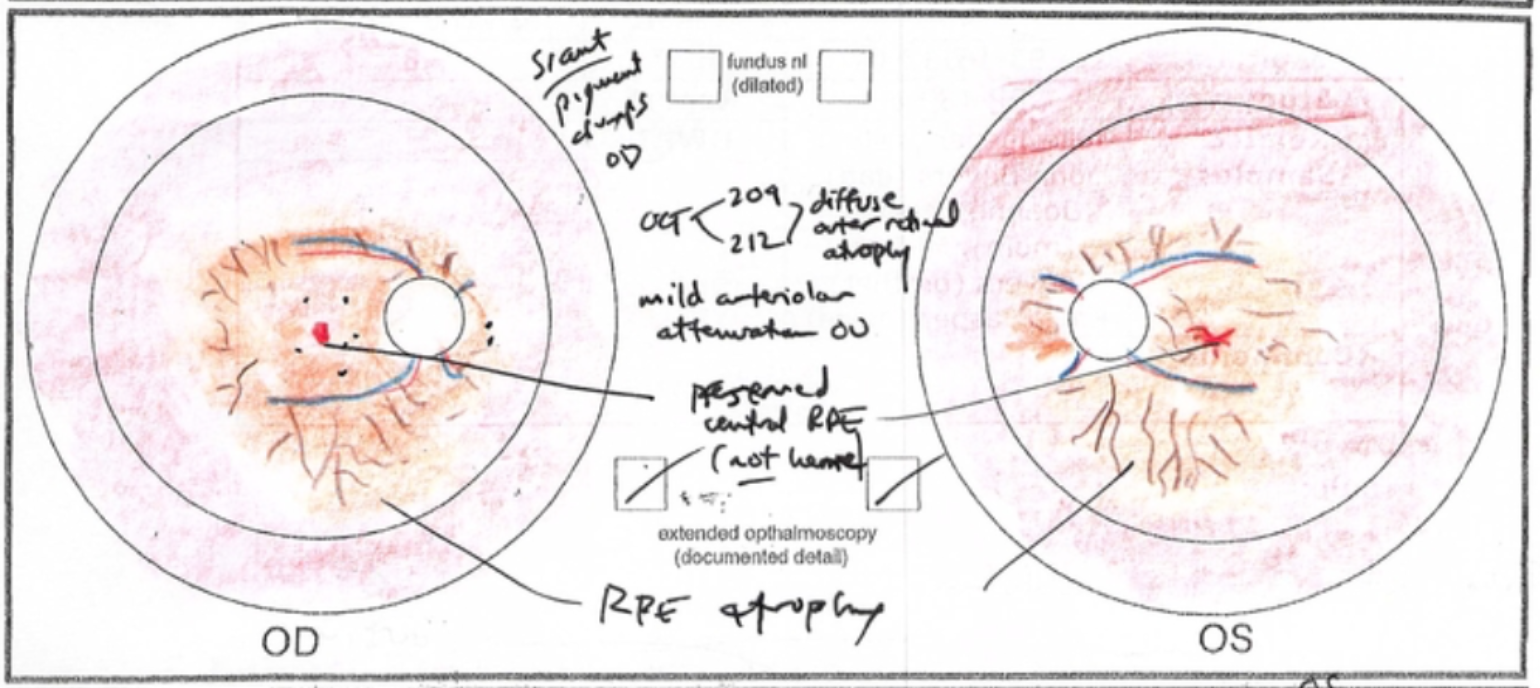

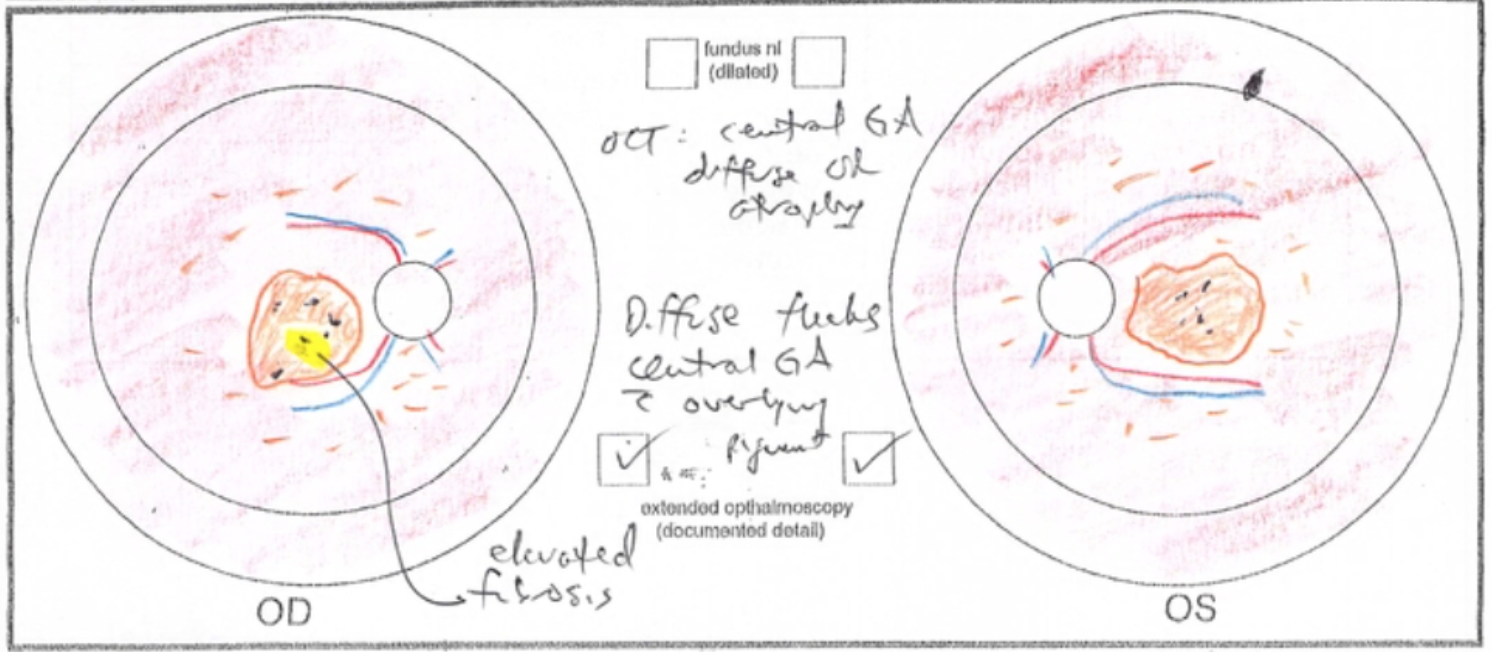

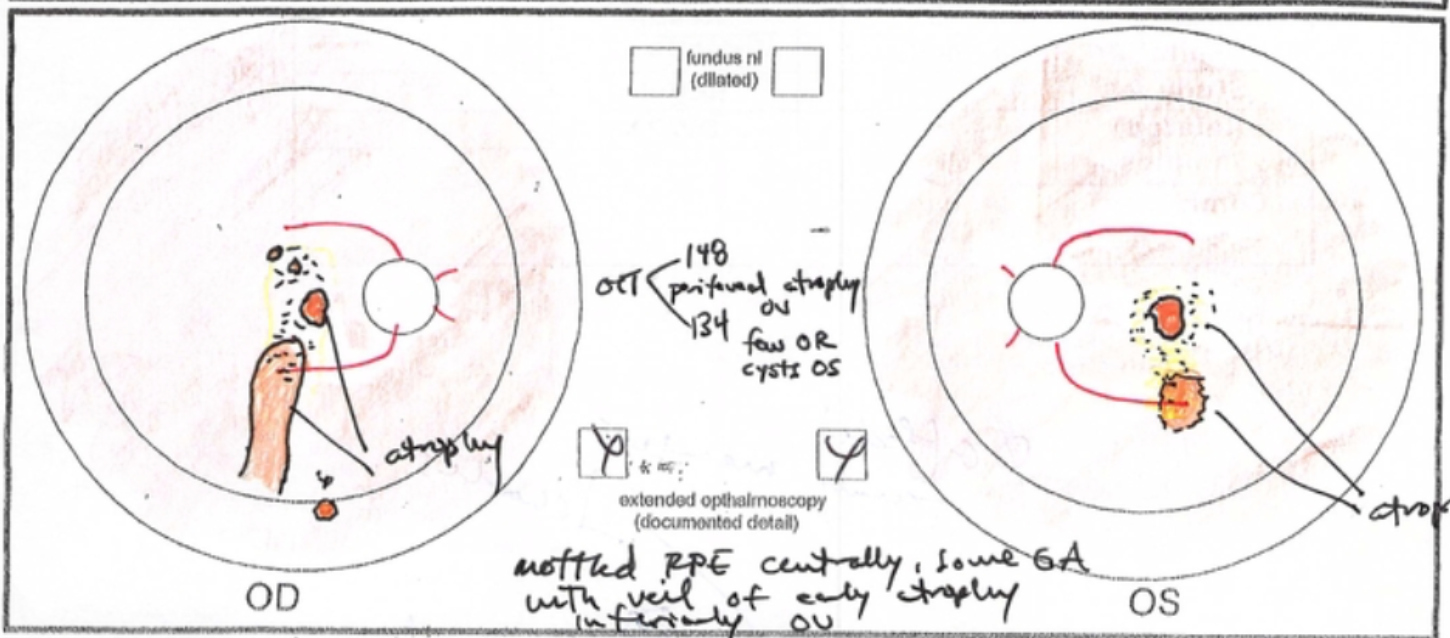

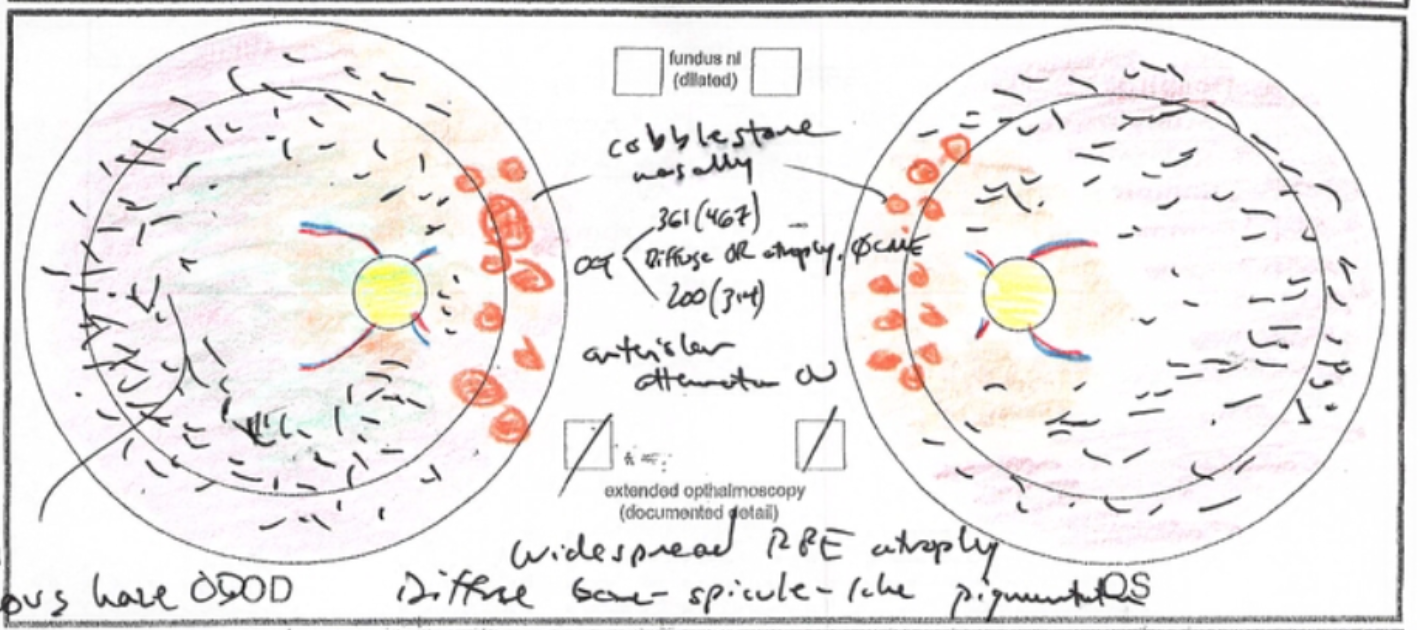

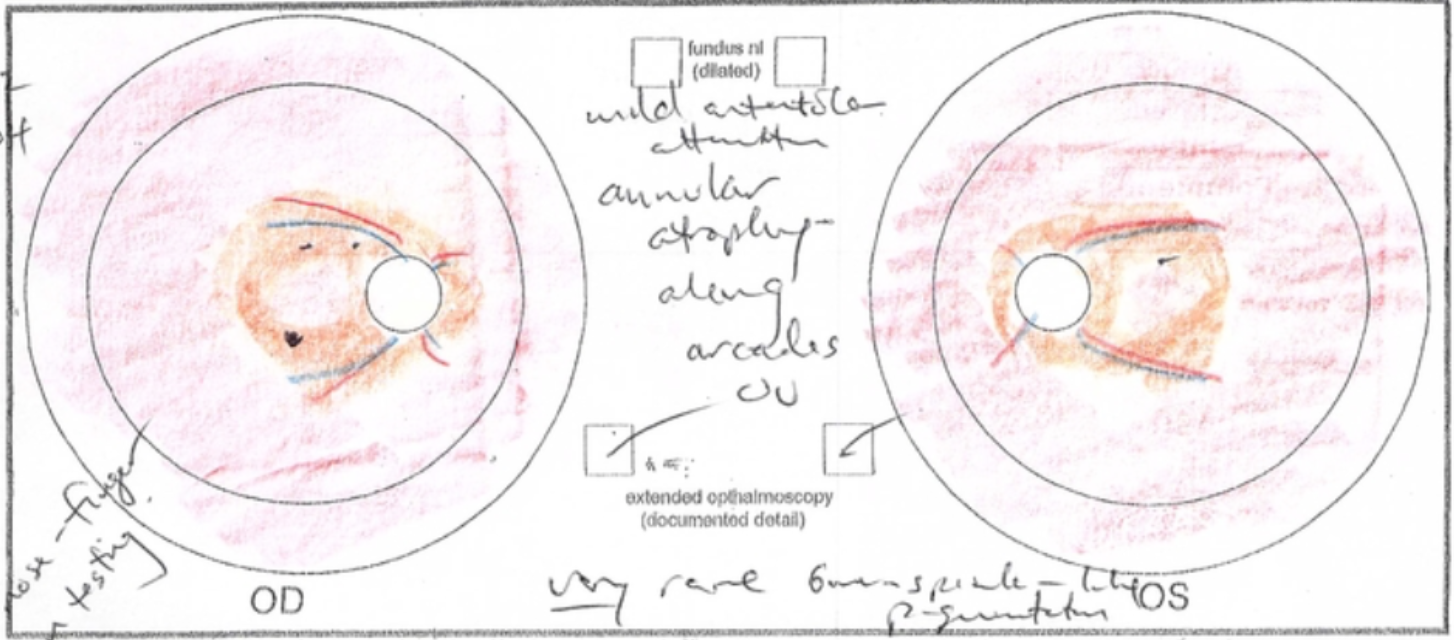

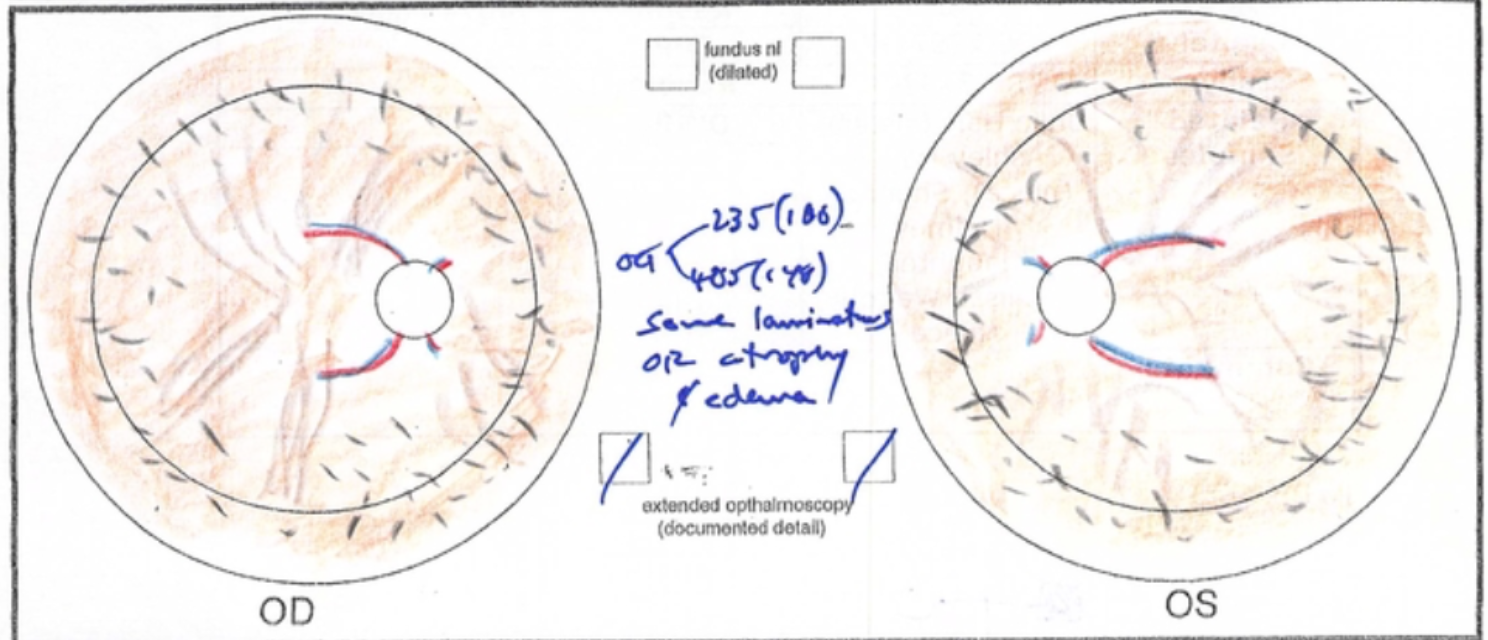

At this center, these cells are then injected into various body parts -- in the macular degeneration patients, directly into the vitreous gel which takes up most of the volume within the eye -- in order to treat the patient's disease.

As an ophthalmologist, I have been asked by patients and friends in the past about similar stem cell clinics, and so I researched them. I quickly realized that what they were selling was scientifically unsound at best, and potentially dangerous at worst, and I advised any who have asked me to stay away and tell their loved ones to do the same. Reading this New England Journal article, I was very sad to see that my concerns were justified.

The three women reported in Dr. Kuriyan's paper not only had both eyes injected under this extremely unvalidated and highly unscientific approach, they had it done to both eyes on the same day, thus exposing both eyes to a risky, unproven therapy -- and they paid $5,000 to do so.

Now, "Who would ever do that?" you might say. And I agree with you, to a point: I certainly never would, and I hope you wouldn't either. But I can understand how it could happen, from a patient's perspective. I dedicate part of my practice to caring for patients with inherited eye diseases, and I see patients with severe vision loss who are desperate for anything to help improve their vision. I regularly speak with family and friends of people who are really struggling with terrible eye diseases, and they so badly want to find something to help. I understand that -- we all feel that way when people we love are hurting.

And this is one of the things that makes me so angry at the people involved in providing this "stem cell treatment." Using pseudoscience (we'll get to this below), they prey upon people's desperation, charge them a not-insignificant sum of money, and offer a solution which any scientist worth his or her salt would immediately recognize as highly suspicious/utter junk.

But that's not the only reason this makes me angry.

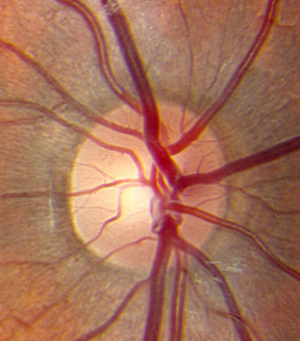

As a scientist who has studied and worked and trained with world-leading researchers at the University of Iowa, I believe that stem cell technology -- appropriately developed, studied, and applied -- is an incredibly promising area. But it will not involve sham clinics where patients are treated for all sorts of different diseases with the same "stem cells." It will not involve patients paying money for experimental treatments. It certainly won't involve having both eyes injected on the same day, and the first patients treated will not be patients -- like these three women -- who had useful vision to begin with, and thus, much more to lose.

Let's discuss stem cells for a minute, because stories like these give this technology a bad name and can erode public trust. In 2012, Japanese physician scientist Shinya Yamanaka was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his groundbreaking discovery that adult, mature skin cells could be reprogrammed to turn back into stem cells. These cells are called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), because they have been induced into becoming cells that can then become a variety of different tissues, like brain, heart, eye, or liver, for example. Think of stem cells as cells that haven't yet decided what they want to be when they grow up.